Holocaust Survivor Who Fled to Bolivia Shares Family Story

Mike Kleidermacher fled with his family to Bolivia after World War II. He grew up in a small Jewish community in Sarnaki, Poland.

Galloway, N.J. — “¿Puedes hablar Español?” (“You speak Spanish?”)

Irvin Moreno-Rodriguez, then an undergraduate student, looked at the Holocaust survivor who asked him that question — an unassuming Polish man eating lunch with his wife who asked the question with perfect Spanish diction.

Moreno-Rodriguez, like students usually are, was nervous. He was just invited to attend a luncheon by the Sara & Sam Schoffer Holocaust Resource Center (HRC) that was co-sponsored by the Jewish Federation of Atlantic and Cape May Counties. Moreno-Rodriguez felt intimidated being surrounded by people who all had harrowing stories of the Holocaust, but he soon found himself sheepishly saying, “¿Si?”

“Ah!” Mike Kleidermacher said emphatically as he pulled out a chair. “¡Bienvenido!” (“Welcome!”)

Moreno-Rodriguez never forgot Kleidermacher’s warmth or his incredible story of how his family escaped World War II by settling in Bolivia, a landlocked South American country.

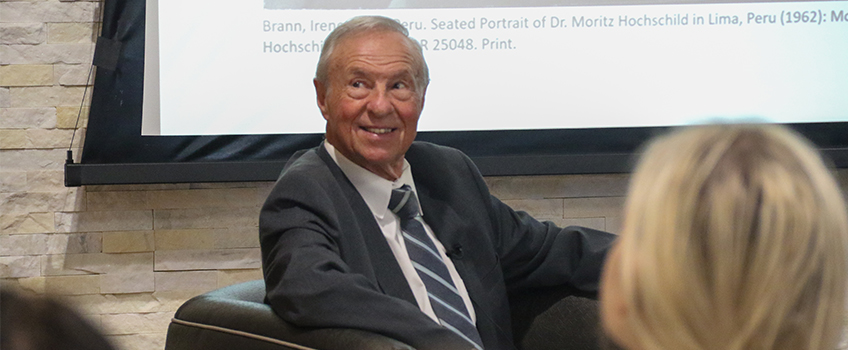

Now the assistant director of the HRC, Moreno-Rodriguez was able to help tell Kleidermacher’s story to students at ¡Jallalla! (Cheers!) — the closing program for Hispanic Heritage Month in the Multicultural Center on Oct. 11.

Escape to Bolivia

Hailing from a small Jewish community in Sarnaki, Poland, Kleidermacher’s family had a relatively normal life before his parents got married in 1939. Starting to feel antisemitic sentiment, his parents and paternal uncle moved to Belarus. After his elder sister was born, the family was displaced and forced to live in Siberia for over a year. They soon found refuge in Georgia, Russia, where Kleidermacher and his little brother were born.

By then, the war had ended, so Kleidermacher’s parents made their way back to Poland to find the families that they had left behind. Unfortunately, only the news of their families’ deaths, ancestral houses being occupied and persistent antisemitism was left for them to find. Seeing that the home they knew was gone, they applied for visas to the United States and stayed at resettlement camps in Germany, Belgium and France before making their way to La Paz, Bolivia. Kleidermacher was only 5 years old in 1947 but still remembers his first day there.

“When I arrived in Bolivia, it was such a strange country, seeing (native Bolivians) dressed differently than us, and I was scared of them. I was holding my mother's skirt,” Kleidermacher said.

Life in Bolivia soon became less scary. His father continued designing and making clothes for a living, his mother shushed him whenever he mentioned the war and they settled in a small Jewish community. He and his Jewish peers attended Hebrew school, went to the synagogue and had bar mitzvah celebrations.

Kleidermacher said he experienced more antisemitism when he was sent to the United States for high school and college than he ever did during his time in Bolivia, though one incident came to mind.

“We had a good life, but we were poor in Bolivia, so I had no toys. My (Bolivian) friends, however, did, so I would go outside every day and play with them. One day, I went out and I went to play with my friend Carlos, who said, ‘Mike, my mom said we can’t play today because it’s Christmas and you killed Jesus.’

“I went to my mother crying and told her, ‘My friends think I killed Jesus, I don’t even know who they’re talking about!’ My mother explained to me the whole story of the Bible and said, ‘It’ll be fine, Mosche, it will be fine tomorrow.’ The next day, Carlos and I got to play again. We’re still friends.”

The Impact of Bolivia on Kleidermacher

Thankfully, that’s the only antisemitic incident in Bolivia that came to mind for Kleidermacher. For him, what he mostly remembers is the friendly spirit of the people there.

“In general, I have to say that the Latin people are very nice. All of them. There's a camaraderie and brotherhood between Latin people,” Kleidermacher said. “That's why sometimes I start with ‘You speak Spanish?’ because as soon as I say that, we connect right away. There’s something there about the common language, and I love that.”

Rosa Perez-Maldonado, assistant dean for the School of Arts & Humanities, mirrored his sentiments about connection during her welcoming remarks.

“I was kind of surprised when I learned a little bit about the history of and involvement of Latin America with Holocaust survivors and how two cultures really kind of intersected with shared common values and support. I think one of the key things that really caught my attention was the kindness and support that they were both able to show each other and how that teaches us something about how we have more in common than what we think at times,” Perez-Maldonado said.

Michael Hayse, associate professor of History, was a part of the effort to create a database that put together over 1,500 stories of various Holocaust survivors who settled in South Jersey. He said working on the project revealed that Kleidermacher’s family weren’t the only ones who found refuge in South America.

More than 20,000 families went to Bolivia when their visa applications to other parts of Europe and the United States were denied during the Holocaust. When South America wasn’t an option, Jewish refugees looked to places like Kenya and Zimbabwe in Africa and the Shanghai ghetto in China.

“It’s important for us to remember, at a time when we once again have one of history’s worst refugee crises around the globe, that Holocaust survivors often survived because they were able to find a place of refuge,” Hayse said. “These are all important stories. Each one is individual, and they’re very interesting.”

Galloway, N.J. – Henry Ackerman only recently realized the extent of his parents’ experiences in Europe during and after the Holocaust.

“She really didn’t want to talk about anything,” said the second-generation survivor from Vineland about his mother, Eve.

Now a new project by Stockton University’s Sara & Sam Schoffer Holocaust Resource Center has brought him closer to his parents than ever before. The center on Sunday launched the Holocaust Survivors of South Jersey Digital Archive and Website at the university’s Campus Center Event Room.

The project, which includes more than 1,500 names of survivors who lived in Atlantic, Cape May and Cumberland counties, has two main components — a digital archive that will reside at the center and a website featuring individual profiles of some survivors.

– Story by Mark Melhorn

– Story by Loukaia Taylor

– Photos by Lizzie Nealis