50 Years of The Argo: Stockton’s Legends of Journalism

By Laurie Melchionne

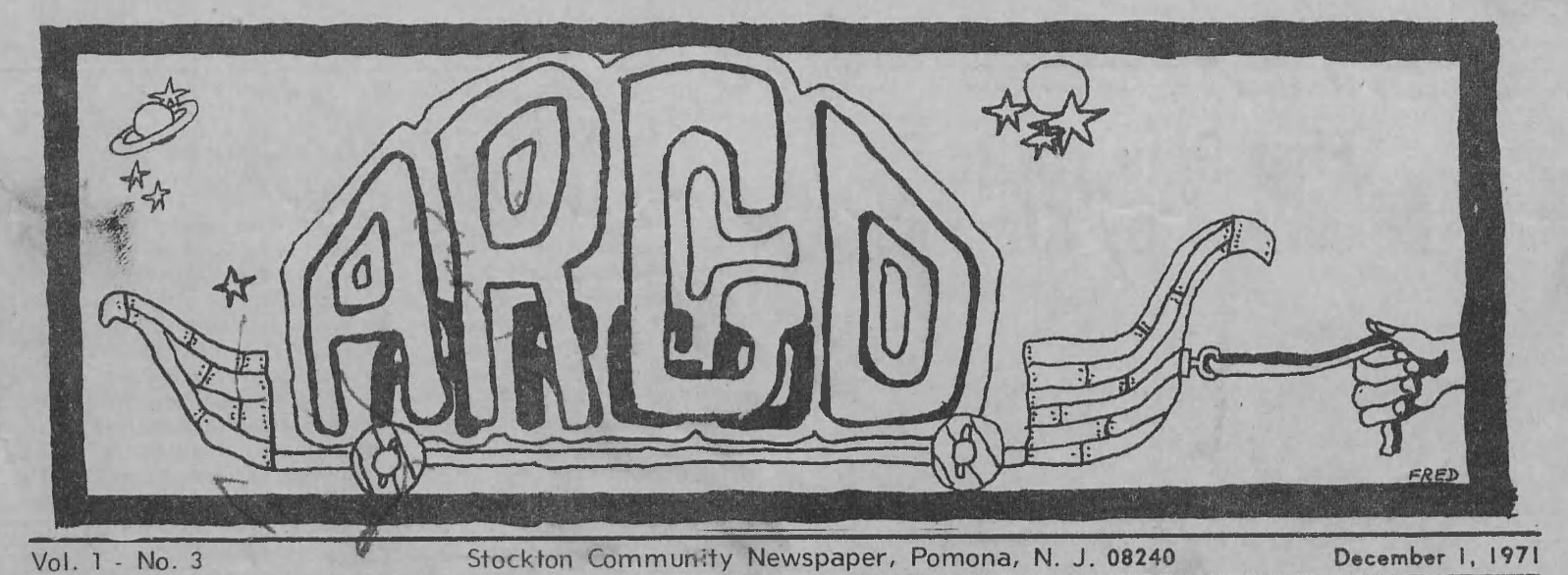

October 2020 marks the 49th Anniversary of The Argo, Stockton’s independent, student-run newspaper. It deserves noting that the university’s official newspaper shares a very close, and significant, anniversary with the institution itself. Although Stockton was originally chartered by the New Jersey legislature in 1969 as a state college, the first classes began in September 1971 in Atlantic City’s Mayflower Hotel. In October of that same year, with the help of then student Dan McMahon and administrator Chuck Tantillo (then assistant to President Richard Bjork), the official independent newspaper was established.

As the current Assistant Editor to The Argo, I hold a special place in my heart for the newspaper. Diving into vintage issues (both in digital and physical archives) is like stepping through a time machine. Every major event in Stockton’s history is chronicled: the fire in the President’s cabin, resident protests and rallies, the establishment of the campus police, etc.

The Argo also showcases significant events in national politics, allowing today’s students to see the ways that Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal, the threat of nuclear war with Russia, and poverty rates under the Bush Administration (to give three examples) influenced the nation and Stockton alike. Thanks to our newspaper, readers can experience these events for themselves as students and faculty once did.

The Argo offers an inside view of what Stockton looked like decades ago, with all of the chinks, triumphs, and controversies that shaped not only a nation, but also made their mark on this once-tiny community in the heart of the Pine Barrens.

Part 1: The Argo is Born

The Argo hit stands for the first time on October 29, 1971, but that’s not what people called it when flipping through its pages. In fact, it didn’t have a name at all. Dan McMahon, founder and first editor-in-chief, along with his initial team, wanted to leave the naming up to the community. In a contest featured in the first issue, students were asked to submit ideas. The eventual winner, however, wasn’t a student, but Professor Demetrios Constantelos. Sound familiar? The Constantelos Hellenic Collection and Reading Room isn’t the only tangible piece of history inspired by this long-time history and religious studies professor. Why out of all the other submissions did Constantelos’ nod to Greek adventurer Jason and the Argonauts perk McMahon’s attention?

It was simple, McMahon says: “I liked Greek mythology.”

But that doesn’t mean what followed was easy. In a recent interview, McMahon detailed the story of The Argo, its early days, and how his experiences at Stockton affected his career for the rest of his life. McMahon contributed a lot more to the paper (and to the college) than bequeathing its Hellenistic name.

“It was a tense atmosphere,” said McMahon, describing the relationship between administrators and students/faculty in the early days of Stockton. “It very much felt like an us against them kind of thing.”

It isn’t hard to imagine the difficulties McMahon encountered when establishing the newspaper, while at the same time maintaining it as an independent, student-run publication that received its funding from the college. In the “tense atmosphere” that McMahon describes, there were many protests and strikes that followed Stockton’s road to the Galloway campus, which was still under construction at the time the first semester rolled around in fall 1971.

Given this environment, McMahon and his friends realized that Stockton needed a medium through which students could share news with and from student voices.

He and his friends plastered flyers for their idea on the walls of the Mayflower Hotel. Did anyone want to see Stockton with its very own newspaper? Would an official publication hurry the college into becoming recognized state-wide—even nationally—by other well-known, competing schools? These questions would be answered in the meeting room of the Mayflower Hotel, where about thirty people showed up to plan.

Before the meeting, and before enrolling at Stockton College, McMahon had attended other schools, where he put his reporting skills to the test. Raised in Oaklyn, New Jersey, he went to high school at Collingswood High, where he got his feet wet at the school newspaper first as a reporter, then as a feature editor. After high school, he enlisted in the navy during the Vietnam War, where he was stationed in Iceland as a radioman. Even overseas, the world of reporting fell easily into his lap. In the navy, he would write messages in old type and used morse code to put words together into sentences.

When he returned to the U.S, the GI Bill® conveniently paid for his college education. He attended Camden County College, where he was an associate editor for their publication, Common Sense. He also worked for the Times Journal Daily, located in Vineland, New Jersey, as well as for the Press of Atlantic City, where he found a great mentor in then-editor in chief, Chuck Reynolds. Despite being a Literature major by the time he arrived at Stockton, he had made his interest in journalism abundantly clear.

This is probably why he felt compelled to see that Stockton had its own paper and that it was done right. Flash forward to that group of thirty people in the Mayflower meeting room: it was McMahon to speak first on the need for Stockton to have its own newspaper.

John Connors, one of his friends from Camden County College, had been listening in the audience when he stood up, faced the crowd, and proclaimed, “All those raise your hands who think Dan should be the editor.”

Chuckling at the memory, McMahon told me, “And everyone raised their hands.”

You can imagine where it goes from here, but Dan had a long road ahead of him. Despite the hot air between students and administrators, it was these very administrators who needed to green-light TheArgo. Dan found that administrator in Chuck Tantillo, the aforementioned assistant to Richard Bjork. Tantillo took McMahon under his wing and granted The Argo its initial funding since the All College Council (the group that approved student organizations) had yet to exist.

“Chuck was great,” McMahon said when reminiscing on how the two got The Argo approved. “But he worked for the president, so I didn’t want his name on it anywhere. I didn’t want him to become an administrative mouthpiece.” It was to be a student-run paper, and Dan was determined to see that it was.

In its early days, TheArgo’s publishing process was as vintage as it gets. Today’s editors use Adobe InDesign on MacBooks, and send each issue to our printer with the click of a button. McMahon, however, used the now outdated hot type method, which I had to Google because I’d never even heard of it before. Hot metal typesetting is a process that inserts sizzling metal into a mold for each word, similar to how a printing press works. Talk about hot off the press!

By 1972, however, McMahon landed on a printing method that, for the time, was state-of-the-art.

A friend from Vineland provided him with access to a photo offset printing press,

which meant good-bye to archaic hot type!

In 1971, campus and public protests against the Vietnam war were frequent in many

parts of the US. McMahon, his colleagues, and even Stockton faculty made their anti-war

feelings clear. A member of Vietnam Vets Against the War, McMahon subscribed to the

Liberation News Service, a publication that frequently showcased anti-war articles.

Whenever McMahon found himself short on submissions, he’d republish these political

pieces in TheArgo.

During this era, when social changes such as abortion laws, gay rights, and civil activism were rippling through society (much as these same issues do today), another political event rocked the already-wounded nation: Watergate.

TheArgo was only a year old when President Richard Nixon’s scandal tore through the media. As with the war, TheArgo voiced the perspective of the Stockton community. A 1974 article headlined “Nixon: Every reason to be deranged” lambasts the former President Nixon as mentally unstable. In that same issue there is an article on Attorney General John Mitchell, a cabinet member also embroiled in the historic scandal. “Bring Watergate Home,” another 1974 article, satirizes Watergate and supporters of Nixon. Public insults in the news? Satire? Scandal? Sound familiar?

Echoes from the early Argos resonate today. When the paper began, a president was facing an impeachment scandal; nearly fifty years later, another president was impeached for the first time since the 1990s. The irony wasn’t lost on McMahon: “We are in the same pickle we were in back then as we are today. We think we are discovering new things, but as Bob Dylan said, ‘It’s all been done before.’ ”

That may be true for the scandals of presidents past and present, but McMahon started things that have not been done before, things that still exist today.

Have you ever heard of Stockpot, Stockton’s literary magazine? Did you know that its direct predecessor was Crying Voices and Unheard Sounds? Can you guess who its founder was? None other than Dan McMahon.

McMahon’s contributions to Stockton in developing a culture that presents unheard voices is deeply significant. In addition to The Argo and the earliest literary magazine, he helped to found the Alumni Association after graduating in 1974, and just to make sure that none of us forgets the man and his legacy, he was awarded a plaque as its founding President—but for us Stockton reporters, editors, and literature enthusiasts, we know him as so much more than that.

Part 2: The Argo Touching Lives

McMahon’s impact on Stockton left an imprint on many lives; some gave root to stories

that have become legends in Stockton history. Eric Sommer was one of them. As a student

who arrived that first semester in fall 1971, Sommer was known as Fred Sommers—that’s

right, the Fred who named our very own Lake Fred (at least in one well-known version of the story),

until a run-in with Queen’s Freddie Mercury made him switch to Eric. Fred was The Argo’s first artist who designed the paper’s first logo. Although Dan suggests that the

first logo should have been a Greek ship more befitting the one Jason steered with

his argonauts—not the Viking ship that Sommer envisioned—the image nonetheless persevered

for many issues. Much like the logo, Sommer himself persevered at Stockton at a time

when tensions among contrasting political views were explosive.

When Sommer was a student, Vietnam was still at a boil. An anti-war school, Stockton’s faculty and students didn’t exactly welcome Sommer when he told people that his dad worked for the government in Thailand and Vietnam (as one of JFK’s “Best and Brightest”) at a time when the violence was bloodiest. This was, of course, after Sommer himself had returned from living in Bangkok for 12 years, after his father was there to “keep the communists out of Bangkok.”

Despite the tension, it was also a time of freedom. Sommer remembers taking classes with professor Brooke Larsen, who now teaches at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. Sommer refers to Larsen as an “intellectual giant,” who honed an art program that made the world feel like it had no boundaries, that creativity among both students and faculty could be hindered by nothing and no one. “I’d leave the motel for class for the day and have to turn around. I’d forgotten to put on my shoes!”

Although Sommer lived in southeast Asia at a time when no one wanted to be there, he never would have turned his musical passion into a career without that specific experience. At the Trolly Restaurant in Bangkok, GI’s on R&R would find twelve year old Frederick playing guitar in the upstairs lounge on Saturday afternoons. One day, Staff Sergeant Jim Hall sauntered in, spotted Fred strumming his guitar, and shook his head.

“‘You’re doing it all wrong,’ he told me,” reminisced Sommer, laughing. “He gave me a set of right finger pics and taught me how to play ‘Freight Train’ by Elizabeth Cotton, honing my skill.” Fast forward to about five years ago, after a career of performing on tour around the world, Fred (now Eric) found Jim Hall’s name on Panel-60 on a Vietnam Memorial at Fort Stockton, Texas where he was playing at The Garage.

Eric went on to tour nationally with top US Acts here and in the EU: Little Feat, John Mayall, Leon Redbone, David Bromberg Buddy Guy and dozens of others, just too many to name here, and was a 40-show vet at The Paradise Theatre in Boston.

The influence of the war impacted many issues—civil rights, veterans’ rights, political ideologies. To Sommer, its impact would last for decades to come.

Part 3: A Platform for Student Voices

As seen in the Berkley College student protests, college campuses around the country in the 1970s fought to draw an old-fashioned society into a new, progessive era. Women’s equality, queer rights, minority issues are just a few examples of the conversations that rocked the 70s and were in full swing at Stockton.

All of this is chronicled in The Argo, and one of the driving forces behind such issues was faculty member Tony Marino, who’s column was called “Faculty Corner.”

Marino, who started writing for The Argo in its first year, was known as “the sex health guy” (Marino’s words). While Vietnam was happening, Marino didn’t participate in the student protests about the war. “That was for the students to do,” Marino told me, recalling that during his time at Stockton, he had his hands full with being a married man and father to a newborn son. Besides, his interests had more to do with issues at home, such as abortion and mental health.

In fact, one of his more famous articles was called “Stockton’s First Suicide,” which

criticized the school’s lack of mental health services and predicted a rise in suicide

rates because of it.

Although he taught many courses at Stockton, such as sociology, demography, and general studies, he originated the first human sexuality course along with psychology professor Jaqui Stanton. It wasn’t long before students came to Marino’s office for pregnancy advice and to ask whether he knew of anyone who could give them options.

Abortion rights, sexuality acceptance, people rebelling against the status quo, an outspoken student newspaper ... it’s clear to see how early Stockton embodies the climate of this era. What’s all the more intriguing is that not only did this happen at colleges all across the country, but it bled into our little community here at Stockton, showing how its early days influenced the progressive, accepting, and liberal arts college it is today.

Part 4: The Argo of the New Century

Fast forward three decades later. The Argo will show you that clubs, offices, and protests abounded in the early 2000s just as they did in the 1970s and do now. In 2006, Emily Heerema became the Editor-in-Chief of TheArgo. Under Heerema, the newspaper featured articles that represented the social climate of the early years of the 21st century. When I spoke to her, she had a lot to say about the kind of news she wanted to share with the Stockton community.

“We wanted to make sure all students were represented in The Argo,” she said. “We were trying to get everyone who was not just a straight white guy to have a voice.”

If one were to travel back in time and meet Heerema while she was a student at Stockton, hearing this wouldn’t come as a surprise. An Orientation leader, the president of STAND, a member of TALONS for SOAR, and an ally for PRIDE events, Heerema immersed herself in the community. She was an advocate for sustainable resources on campus and other environmental-friendly articles, which is why stories from organizations like SAVE and the Surf Club were frequently seen under Heerema’s supervision.

“I would have loved to be involved in even more, but The Argo kept me pretty busy.”

Having her hands full as the Argo’s editor-in-chief didn’t stop Heerema from contributing to the community, both near and far. When Hurricane Katrina devastated the New Orleans area in 2005, Heerema accompanied Bill Hassall, leader of WaterWatch, to stay at a mission church in New Orleans and help with a clean-up following the hurricane. Heerema’s history with student activism, not only relating to environmental issues but also social and political issues of the day, are featured in The Argo. In one randomly selected issue from April of 2007, such activism is featured on almost every page.

The front cover alone is taken up by an article lambasting racist graffiti on campus. Within the issue is a story condemning the 2005 Real I.D Act as Fascist, as well as a piece called, “Pride Alliance: Is New Jersey a Safe Zone for Gays and Lesbians?” There was also an article on the Social Work Club, something that directly reflects what Heerema valued in her community. Issues of gender, race, and sexual identity, as portrayed in this vintage Argo issue, were just as relevant then as they are today.

In the early days of The Argo, global political crises like the war in Vietnam and the threat of nuclear war rippled through the pages of the newspaper. More recently issues of social identity have made their way into the paper as they do to this day.

But there are connections to be made. In the early issues of The Argo, Tony Marino was writing about social and sexual health, and the lack of services on Stockton’s campus; in Heerema’s time as editor, issues of women’s sexual health, women’s history month, and suicide awareness were as commonly seen in the early 2000s as they were in the early 1970s.

“We were all feminists on The Argo,” says Heerema. “In 2008, there was not a lot of talk about more than two genders, but LGBTQ was a big deal in The Argo.”

For all the social issues in The Argo during this time, Heerema made sure that global political issues weren’t swept under the rug, either. In the aforementioned issue, there was a blurb on the genocide in Rwanda, which, at the time of publication, had happened thirteen years prior. Heerema made her opinions on genocides and oppression around the world known, which is why, in addition to her bold publications in The Argo, she participated in student protests like the B-Wing “die-in” in respect for the genocide in Darfur, a region in Sudan where millions of men, women, and children were slaughtered in 2003, and was the start of Sudan’s ongoing humanitarian crisis that still exists today.

At the time of Heerema’s editorship in the mid 2000s, wartime news had shifted to the conflict in Afghanistan. Stockton’s approach to war, soldiers, and veterans had also transformed. No more would students like Eric Sommer be condemned for having family members associated with the military. “There were no major protests about the war,” Heerma recalled. “Stockton was super welcoming to veterans, as they are today.”

However, that didn’t mean The Argo didn’t welcome controversial subjects about patriotism. For example, a student submitted an op ed suggesting that 9/11 was fake which Heerema promptly published. While there wasn’t much about the Afghanistan war in terms of student protests—Heerema admitted to not being a supporter of the war like many at the time—there were many articles that covered the conflict in Syria.

Conclusion

Today, The Argo is a vastly different newspaper than it was in 1971. Today, we don’t use the hot-type that Dan McMahon utilized to print onto the page; in the comfort of our own office in the Upper Campus Center, we put graphic design skills to the test on Mac desktops with InDesign. With the click of a button, we send a print-ready pdf to our printer, School Paper Express, who delivers it to the mailroom on Monday of each week.

For all the technology that makes our lives as editors easier, assembling a newspaper every week doesn’t come without its complications. The end of the Spring 2020 semester marks the first full academic year that Alexa Taylor (current Editor-in-Chief) and I are at the helm. Replete with graduating staff, hiring people to new positions, shipping issues, and color mix-ups, running a newspaper isn’t the easiest of tasks.

This is amplified by the undeniable fact that the newspaper is a dying medium. With social media dominating the lives of today’s students, the digital age has had a great impact on the motivation to read traditional, in-print journalism. However, Stockton students have kept The Argo afloat with their unabashed passion for sharing news, events, and creative stories with their community. Devotion to the craft of journalism pulsates in the halls of our university; this is what makes my job as Assistant Editor so exciting.

In the end, it was The Argo legends who paved the way for all of this, and Stockton couldn’t be more grateful.

* GI Bill® is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). More information about education benefits offered by VA is available at the official U.S. government Web site at http://www.benefits.va.gov/gibill.