Shellfish Farmers Foster Oysters for Conservation

Kristin Adams '17, a conservation and aquaculture specialist for the Ocean County Soil Conservation District, and Elizabeth Bick, a Stockton Marine Field Station assistant, gather water quality data at an oyster lease before seining.

Port Republic, N.J. - New Jersey shellfish farmers from Tuckerton to Mantoloking are getting paid to foster oysters for conservation alongside market oysters sold in seafood restaurants through a $961,227 award from the U.S. Department of Agriculture–Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP).

The RCPP funds private and public partnerships for conservation; in this case, contributing to the restoration of rare and declining natural communities of oysters.

Kristin Adams ’17, who studied oysters as a graduate student, was awarded the grant to involve commercial growers in the restoration of the bay. The oysters that grow up on commercial leases will move to two restoration reefs monitored by the Stockton University Marine Field Station.

Adams is a conservation and aquaculture specialist for the Ocean County Soil Conservation District and a U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service partner. She brought Stockton on board to help monitor changes in water quality and to sample marine life on and off the participating oyster leases with seine and gill nets.

Adams first studied biodiversity surrounding oyster farms in the Barnegat Bay as a Professional Science Master’s graduate student.

She sees bivalves as a beacon of hope for bringing back a healthy bay ecosystem with their ability to filter water and provide habitat.

The four-year pilot project began this year with nine farmers fostering baby oysters, known as spat, from June through November. The spat are currently growing on shell in floating mesh bags or bottom trays in the bay.

Baby oysters grow by sticking themselves to a hard substrate.

The spat-on-shell method gives oysters a head start. The larvae grow up in tanks on land that are filled with shell. Once the larvae stick to the shell, they are moved to the oyster leases to grow up in the bay.

Spat on Shell

“For most of the producers, spat-on-shell is new. They are used to growing the single cocktail oyster for raw bars where they use single oyster seed to grow a beautiful, tasty product for restaurants. This is a different technique and gives producers with smaller leases a way to farm for restoration,” Adams said.

In late November, the farmers will plant the foster oysters on two conservation reef sites, the Mill Creek Reef and the Tuckerton Reef.

Back on the Barnegat Bay with Stockton

As a Soil District employee, Adams works with private landowners to implement conservation practices such as no till, creating pollinator habitat and managing forests.

Growing up on Long Beach Island, the saltwater is Adams’ second home, and that knowledge of the bay has extended her work into the water. The oyster is her strategic partner in promoting sustainability and helping to improve the health of the bay ecosystem.

Seven years after graduating, oysters brought Adams back to the Marine Field Station.

This August, she joined Christine Thompson, associate professor of Marine Science, and student researchers Landon Gedes and Samantha Gransee to monitor water quality and sample biodiversity with a seine net at an oyster lease in Great Bay.

Thompson explained the partnership as paying experienced shellfish farmers to use space on their leases “to foster oysters” for conservation.

“Stockton’s role is documenting the ecosystem services at four of the oyster farm sites and then long-term monitoring at the reef sites, “she added.

She got approval to use gill nets for sampling to avoid the bias created by fish traps structures that attract fish seeking protection.

On a warm summer day, wearing full wetsuits to ward off greenheads, the team jumped into the bay to pull a seine net along the submerged bags of oysters.

The creatures caught were emptied into a holding tank on the R/V Rudy Arndt to be identified, weighed, measured and then released.

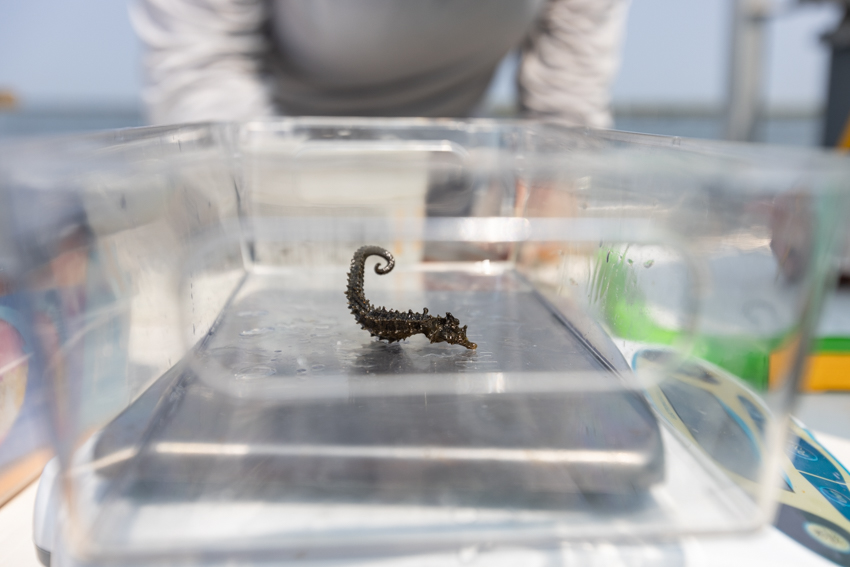

The star of the show was a seahorse that blended in with a clump of brown macro-algae. Comb jellies and Atlantic silversides were the most abundant catches, and a tautog and pipefish were other species represented.

A control site was sampled for comparison purposes. In theory, biodiversity should decrease with distance from the oyster lease, which provides hiding spots and safe nursery habitat.

Bottles were filled with 100mL water samples at the lease and control site to be studied back in the lab.

Sea the Difference

“We filter the water samples through a glass fiber filter, which retains the suspended sediment in the water,” explained Thompson.

The tinted circular marks left on the filter paper represent how much sediment or algae was in the water sample.

The darker the color, the more sediment was suspended in the water.

Visualizing the Impact of Conservation

Filter paper illustrates the difference in turbidity between water samples.

“We are looking to see if the water is clearer on the reef sites. Last year, some of the areas surrounding the Tuckerton Reef were significantly clearer than the control and that’s indicative of the filtration capacity. And you can see it,” Thompson said.

Student Experiences go Beyond the Books with Boat Trips to the Bay

Landon Gedes, a senior Marine Science major from Montgomery, N.J., didn’t know about oysters beyond the ones he’s ordered out, but after Biological Oceanography with Professor Thompson, he started to learn about their lifecycle.

At 5 a.m., Gedes got to the dock on Nacote Creek for a gill net sampling session at one of the oyster leases. He heard a swan family walking across the crushed shell parking lot as he looked up at the moon setting over the saltmarsh and Jupiter and Mars aligned in the clear night sky. A bait ball splashing drew his attention down to the water.

“The surface was shiny with brief flashes. It looked like glitter,” he recalled.

The light show in the bay was performed by bioluminescent plankton.

Gedes said that the early wake ups are worth it. He’s plucked his fair share of crabs from the gill nets and witnessed evidence of a larger predator, likely a shark, that swam with force through the net.

He’s thankful for the opportunity to get more comfortable working on boats doing research.

Who Lives on the Oyster Lease?

Christine Thompson and Samantha Gransee identify, process and release the fish caught while the rest of the team seines along the next stretch of the lease plot.

Samantha Gransee, a Marine Science major from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, has worked on oceanography research mapping inlets and helped curate a shell collection, but hadn’t dove into the biology side of her major until this summer when she took the opportunity to go gill netting on the oyster leases.

She learned knot-tying techniques and how to process fish on the measuring boards and weighed them on the scale.

A Win for the Oysters is a Win for the Bay

Dale Parsons Jr., a fifth-generation shellfish farmer, calls the opportunity a “win-win-win-win.”

When he was growing up, restoration was unheard of, but now it’s a necessity. He noted the project educates farmers, restores habitat and equips growers with the spat-on-shell growing method that offers a noncompetitive revenue stream for a product that is not sellable on the seafood market.

Federal dollars are coming into New Jersey and giving farmers a way to sell oysters that are less than a year old, too small for restaurants, but full of filtering and habitat potential when planted on a conservation reef.

“There are few opportunities where oyster farmers can work together,” Parsons explained, but conservation is a team effort and the grant project is looking to reach enough farmers to make a difference in the bay.

“It's not for my immediate benefit. It's for generations down the road, whether it be my daughter or someone else's children, if they decide they would like to venture out to the bay to experience what it is to produce income from a limited resource, they're going to have a place to work,” said Parsons.

The impact of the project is measurable. Parsons calls Stockton the “biological auditors” who are answering the questions. “What are the improvements? How efficient is this? What can we learn from the monitoring data,” he asked.

Parsons has been involved in Stockton’s oyster conservation efforts since the creation of the Tuckerton Reef in 2017.

Planting in the Bay

Dale Parsons and his team plant oysters on the Tuckerton Reef in 2020. A barge transports spat-on-shell to the reef site where they are sprayed with water power into the bay.

“There were no oysters in the bay for a number of decades due to disease pressure. Now we have an oyster that is resistant to the diseases, and we have the opportunity to use that oyster to produce a habitat that would extend this resource much more than it normally would,” Parsons said.

He used one of his own clam leases in Great Bay as an example of the oyster’s ability to keep the bay thriving.

“The lease was historically an oyster lease back in the '30s, '40s and '50s before the diseases came into the bay and wiped everything out. There are no live oysters there now because of the disease that killed all natural oysters, but there are shells left behind from those dead oysters that provide habitat for the highest population of clams per square foot than anywhere else in Great Bay,” he said.

Although the oysters died out, their shells allowed other species to survive.

"Having that shell hash provides a surface for that tiny clam to bissel to (attach by a thread), and once they grow large enough, they can fall down to the bottom and burrow in that shell hash and be protected from crabs and other predators,” Parsons explained.

Parsons noted that there is one constant in the bay. “The one concept we can always depend on is that if you have a good bed of shell you’re going to get some recruitment.”

Learn more about Stockton's Marine Field Station and how it provides coastal teaching and research opportunities for students in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics.

Story and photos by Susan Allen