Do ‘Immortal’ Women Owe Us Their Cells: The Case of Henrietta Lacks

(L-R): Donnetrice Allison, chair and professor of Africana and Communication Studies; Terrilyn Battle, assistant professor of Counseling; George De Feis, assistant professor of Business Studies; and Trina Gipson-Jones, assistant professor of Health Sciences.

Galloway, N.J. — The study of polio, AIDS, tuberculosis, and even COVID-19 treatments and vaccines all have one thing in common — the use of an unwitting woman’s cells that doubled and tripled in size, providing researchers with the perfect test subject.

The cells not only provided multiple blank slates for medical professionals to test different medicines, but how the cells were taken demonstrated the lack of care or information given to Black women in the health care system.

Funded by the Compass Fund and the University Foundation, the Interprofessional Education Committee hosted a panel discussion on the implications of researchers utilizing cells without gaining informed consent from their patients in the Campus Center Theatre on Feb. 28.

The ‘Immortal’ Woman

Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman from Clover, Virginia, was diagnosed with cervical cancer in the 1950s and sought treatment from the only hospital in the area that allowed “colored” patients: Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Despite the oral histories and/or myths about doctors who snatched Black people off the streets for research purposes, Lacks trusted that the doctors in the hospital would do anything they could to help her survive for her husband and five children. They did, but to no avail as Lacks died at 31, just nine months after treatments began. Her body would soon be buried in an unmarked grave next to her mother in a family cemetery.

However, her cells would live on.

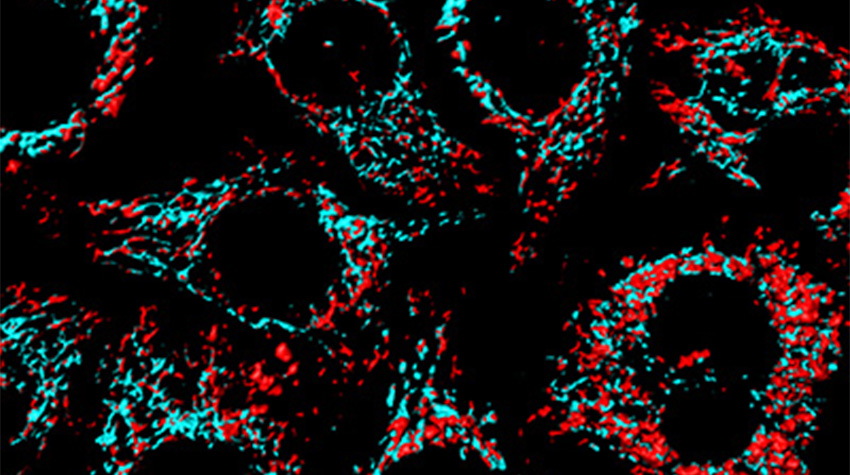

Her cells — nicknamed “HeLa” — would go on to travel the world and even space in culture jars. They helped researchers discover multiple cures and treatments for diseases that have plagued humanity since the beginning of time due to their resiliency and constant repopulation. The HeLa cell is so powerful that it immediately and regularly “invades” other cells that are just near it in a laboratory, leading to scientists having to isolate her cells to prevent contamination.

Even though Lacks died in 1951, her cells are still multiplying endlessly, earning the moniker of “immortal.”

Lacks’ descendants would not know anything about their mother’s “donation” to science and how her cells have saved countless lives until the 1980s, almost 30 years after her death. After finding out, the family has been routinely bombarded and harassed by medical professionals looking for more blood from the family and advantageous “lawyers” who claim that they can receive reparations to the tune of $6 billion.

Her body would soon be buried in an unmarked grave next to her mother in a family cemetery. However, her cells would live on.

The Case for Utilitarianism?

In discussing Lacks’ case, some medical professionals turn to a utilitarian philosophy: the ends (valuable cures and treatments previously undiscovered) justify the means (collecting a woman’s cancer cells without her knowledge and informed consent).

However, when asked by Political Science major and moderator Vera Tagtaa if the utilitarian theory of ethics applied to Lacks’ situation, there was a resounding “no” from all four panelists at the discussion.

“When you open it up, and you start thinking about it — yes, they have millions of cures that can be directly related to the HeLa cells and they have helped countless people, which is awesome — but whom have they harmed?” said Trina Gipson-Jones, assistant professor of Health Sciences. “They harmed the family and the community. When you think about delayed treatment, medical mistrust, health disparities, not even seeking health care and other poor health behaviors: they can all be related back to stories such as this. Do the ends justify the means? I’m not sure about that.”

Donnetrice Allison, chair of Africana Studies and professor of Communication Studies, agreed with Gipson-Jones and brought up the fact that, despite the good that her cells did, Lacks’ case demonstrated medical racism and a lack of informed consent collection.

“Look at the harm that was done to her family, just based on the racism that is ingrained into the health care system for (the doctors) to even think, ‘We don’t need to regard these people’s feelings about any of this, we don’t need to ask,’” Allison said. “At the end of the day, she may have agreed to participate, but they didn’t even give her that opportunity. What is the oath that doctors and nurses take? First, do no harm, right? So much harm unfolded because of that.”

“Without that consent, there should be no one profiting from someone else’s being. Any parts of it, even the smallest part (of the body) such as a cell."

The Ethics of Profiting from One’s Body

Tagtaa presented another question to the group: Should individuals and/or their doctors be able to profit financially from different parts of their bodies, like cells? For George De Feis, assistant professor of Business Studies, and Terrilyn Battle, assistant professor of Counseling, the answer is yes, depending on consent.

“People profit from their inventions, creations and patents all the time,” De Feis said. “Walt Disney is still making money off of Mickey and Minnie (Mouse) many years after his death. There are lots of benefits from patents and trademarks, but for your own cells? Why not?”

When thinking about the question, Battle placed herself in Lacks’ shoes: Would she have wanted to possibly benefit from the use of her cells if the opportunity presented itself before research on her cells began? Would she have wanted her descendants to reap the benefits in her stead?

“For me, it comes back to that consent and the ethics of this,” Battle said. “I think it’s different when you are a donor making that conscious decision, but she didn’t offer to be a donor. With consent, yes, but without it, definitely no.”

“Without that consent, there should be no one profiting from someone else’s being,” Gipson-Jones said. “Any parts of it, even the smallest part (of the body) such as a cell. If other people are benefiting and the person who gave their entity or their cells, or even their family, does not benefit, that’s not justice or equity.”

Lessons from Mrs. Lacks’ Story

Each of the panelists agreed that Lacks’ story is full of valuable lessons for all students.

“The book is a great and excellent tool for students, especially those interested in health professions,” Gipson-Jones said. “It’s a cautionary tale in regards to how we should be treating patients and how we should always uphold ethical principles. It is also a story of resilience and a way in which we can examine, in a real-life story, the impacts of social determinants in health.”

“Certainly, we have seen many experiments and tests the last hundred years, such as the Milgram Shock Experiment, Syphilis studies at Tuskegee,” De Feis said. “(Uncovering) all of that has helped to make it a more perfect profession, but there’s still a ways to go.”

“Both the book and movie are good for students, not only going into physical health care but those going into mental health fields and social workers as well,” Allison said. “It’s not a simple lesson: look at all that unfolds after that and the people impacted by that act. You get a sense of the family of someone who was experimented on, and you realize that there are other people affected by that.”

“I talk to my classes a lot of times about empathy and if it is learned or innate,” Battle said. “And I think that this movie conveys what empathy is. I find it hard to watch the movie and not be moved by the impact that this research had on the family.”

– Story and photo by Loukaia Taylor