Wendel White Highlight

November 3, 2025

Photo on left: Wendel White, Guggenheim Fellow Photographers, and Laura Auricchio, Vice President of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, at a presentation during the Diverse Perspectives in Photography: Four Black Guggenheim Fellows in the Philadelphia Region exhibit (Stockton University Art Gallery). Credit: Allison Wilson.

Tell us about your background, your education, and then how you got into art.

I started working with photography as a high school student at Montclair High School. The art teacher who introduced me to photography showed a documentary film about the photographer Dorothea Lange, which had a powerful impact on me. There are many ways in which that documentary influence has stayed with me today.

I went to the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York as a photography major. After SVA, I attended the University of Texas at Austin for graduate school.

What inspires you in your work today?

I am interested in experimental photography, documentary photography, and commercial photography. I often look at advertising images and what people are doing in advertising photography. I think that comes from the range of experiences I had in school, studying with so many different photographers. The work that I do has been influenced by documentary fine art work, and that's been what has played out in my work today.

I look at photography as a way to possibly expose people to a language.

What brought you to Stockton?

During graduate school, I studied with the photographer Mark Goodman. We often spent time talking about photography outside of the classroom. We even had some opportunities to photograph events together. I remember going to a rodeo, which, you know, coming from the East Coast, I hadn't seen anything like that. It was those experiences that really made me think about possibly pursuing an academic life as a way of working. The idea that I could work with students and pass those experiences on was very appealing.

My first teaching opportunity was back at School of Visual Arts, teaching a technical photography course as an adjunct. I also had a wonderful opportunity as a volunteer educator for a group that placed people in different community institutions. I was placed at the Bellevue psychiatric hospital in New York, where they had a high school embedded in the hospital. I also offered workshops at the International Center of Photography. All of these opportunities lead me to feel that the academic setting would be a good match for my goals and skills.

Even though I was also doing a wide range of commercial projects, the educational component was always there. I then looked for opportunities that would let me commit full-time to teaching, and Stockton was the place that connected with me.

How do you find that balance between working on projects and teaching?

I always thought that teaching at the university level is an opportunity to work with and encourage students to possibly pursue something that I'm very passionate about, or to just be exposed to it. I look at photography as a way to possibly expose people to a language. Students often take a semester of French, or a semester of German or Spanish. Students might take a semester of a “visual language” that they might be somewhat familiar with (images all around us), but not in the way that we'd like to immerse you at the university level.

Also, it is an experience that has provided me with time and resources, and opportunities to continue to pursue working independently as an artist, and to continue to advance my professional activity.

I've been very fortunate with support from the institution, through internal awards, and through large numbers of external awards from different entities: the New Jersey State Council on the Arts has awarded me four grants; the current exhibition is in connection with the Guggenheim Fellowship; and most recently, I received the fellowship at Harvard. Those recognitions are encouraging and have pushed me forward. It’s helpful to be sustained by responses from people beyond yourself.

I find that working with my students also feeds the work that I do. So, when I sit and help them solve a problem, it triggers a thought about how I might solve a problem for myself.

Can you tell us about some of your more recent projects?

When I talk about my work in a public setting, I talk about how important an early project was. I was at Stockton three years before I started working on Small Towns, Black Lives, traveling around South Jersey, and documenting the small, historically African-American communities. It started with one town, which was Whitesboro.

When I first arrived at Stockton, I was surprised by the opportunity to be in an interdisciplinary environment. Having the opportunity here to really interact with faculty from different disciplines prompted me to think about all the different ways in which these stories that I was encountering in these small black settlements throughout South Jersey were made up of history and architecture and landscape and geography and a whole range of different ideas. Different people interacted with me about the work, and about bits and pieces of these stories. That environment provided a foundation that led me to the other projects I've worked on.

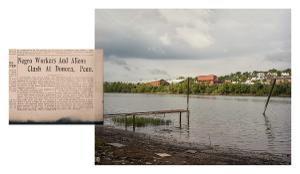

By the time I went to work on Schools for the Colored, I gradually evolved to thinking about architecture as a way of describing Black experience and a range of school sites throughout five of the northern states in the United States. I returned to this idea of the landscape in the history of the “Red Summer” events that took place in different parts of the country, and combined the photographs with historical newspapers in the Red Summer portfolio.

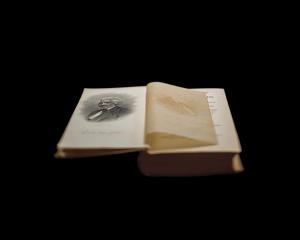

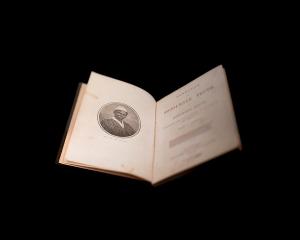

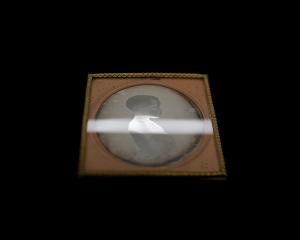

The most recent project is Manifest: Thirteen Colonies in partnership with Harvard and the Robert Gardner Fellowship. I had been making photographs in public collections of the remains of material culture collected all around the country. It started with an experience at the University of Rochester. I came across a lock of Frederick Douglass's hair in the collection at the University of Rochester, which they allowed me to photograph, and I was just knocked out by the idea that I was sitting at a table in front of a piece of Douglass's body.

It sparked this idea of exploring what's in public archives that tells the story of

Black experience and African Americans in the United States. When the opportunity

came to propose a project for the Gardner fellowship, I narrowed the concept because

I had worked on a project with Monuments Lab in Philadelphia as a preliminary to the

250th celebration here in New Jersey.

With the Gardner Fellowship application, I thought, “This would be an opportunity to work on a project that specifically looked at the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence as an inflection point in the history of race in the United States”. It would offer a response to indicate that 1776 was complicated because of the way in which the unity of the United States was necessarily bound together by eliminating any conversation about slavery. I thought, “What better opportunity than to travel around the thirteen original colonies and have samples from each one of those colonies as they exist today?”.

All of the Manifest work was influenced by my project titled Small Towns, Black Lives.

Can you tell us about the exhibit, Diverse Perspectives in Photography: Four Black Guggenheim Fellows in the Philadelphia Region, at the Stockton University Art Gallery?

Reaching back almost 20 years, this exhibit came out of a conversation with the curator, A.M. Weaver, at the Noyes Museum before the museum became part of Stockton. The Small Towns, Black Lives Project was their 20th anniversary exhibition. In conversation with her, she came to realize that there were only a handful of African Americans who had received the fellowship in photography.

She passed away in the intervening years, but it came up again in a conversation with Don Camp several years ago at the Berman Museum. There was an exhibition of William E. Williams' photographs, and, to supplement his exhibition, the museum organized a panel discussion with the four Black Guggenheim Fellows from the Philadelphia area.

The four of us talked about our experiences in photography. In fact, we have transcribed and reproduced that conversation in the catalog for the exhibition, because it was so important in terms of inspiring the exhibition.

In this exhibit, there are traditional analog photographs by Williams (darkroom prints); my digital prints; Ron Tarver’s prints that are a combination of digital and printmaking; and Don Camp’s work has a further combination of digital and traditional printmaking in his images as well.

It wouldn't have come together without the support of the institution, but specifically, the support of Ryann Casey, Allie Wilson, Amanda Cantillon, and the student workers in the Stockton University Art Gallery.

What do you hope Stockton and the greater community will take away from this exhibit featuring Guggenheim fellows?

We have this wide range of talent in this area that has been recognized by one of the premier fellowship opportunities for scholars and artists. We make artworks about our experiences, and those experiences are played out in all the different practices: Ron's work, which is so personal about his dad; Don, who is making portraits of people, and we see these faces looking back at us, showing how powerful faces are; and then both William and I are driven by research-based projects. How remarkable it is that there are artists who are all in this relatively nearby geographic region that happen to all be African American, recipients of the Guggenheim fellowship, and continue to be really active in our practice.

Anything else that you would like to share?

I've been very fortunate. I have a group of colleagues that I've worked with over the years in the visual arts program and in the School of Arts and Humanities who have been so supportive and collegial. I really appreciate them and the opportunity to work with students who might have less access to art resources than students at a New York or Philadelphia school. It's really rewarding to work with students who may not otherwise be exposed to these opportunities.

Wendel White's Featured Pieces

Story by Michelle Wismer