Picture Stockton… digging for clues to the past

Cape May Court House, N.J. - When students enroll in Bobbi Hornbeck’s Archaeological Field Methods course, they become project collaborators for the Museum of Cape May County’s Digging History Project.

The museum has questions about the property’s past, and students get hands-on experience digging for the answers.

The museum is situated on land that was part of the Indigenous Lenapehoking territory and includes the colonial era Cresse-Holmes House, a barn and a research library.

In his time, the property owner, John Holmes, was the second wealthiest person in the county, a financier of privateer ships in the Revolutionary War and a co-owner of at least one salt work in Cape May County, but Hornbeck suspects there is more to his story.

“We're looking for evidence of maybe a merchant store that sold goods that were necessary during the war like iron, or nails, or musket, or maybe he was involved in ship building on his property,” she said.

The museum also wants to better understand the lives of the enslaved people who lived and worked on the property until they were manumitted by Holmes’ son.

The assistant professor of Archaeology’s students start learning about the curation process in a classroom setting. They catalogue museum artifacts to support future research by taking measurements with a caliper, recording weight, and documenting field tags, color and short descriptions.

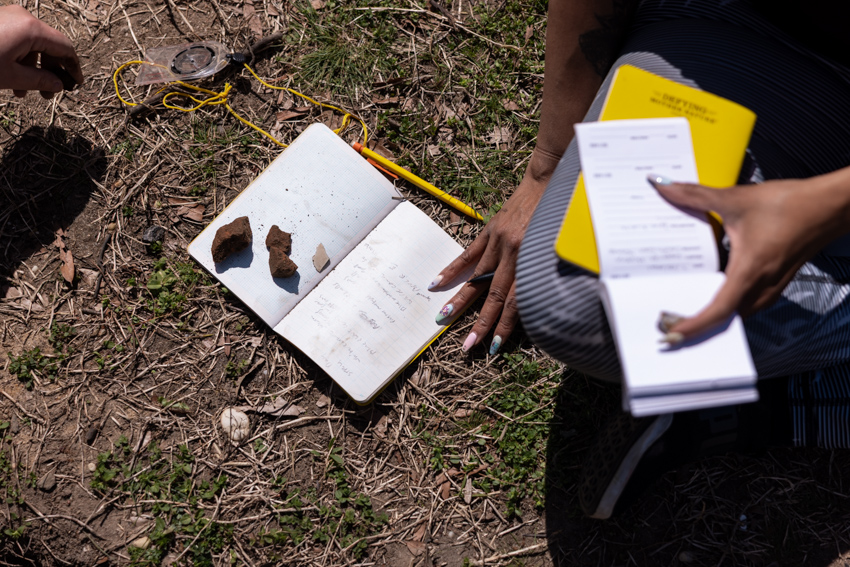

The exercise is practice for the day when they unearth real artifacts from a culturally significant site.

“Reading about what other people are doing is the hardest way to learn how to do archaeology. If you can't feel the changes in the soil with your hand, it's like you’ve reached a dead end just talking about it in class,” she said.

That’s the point in the semester when the museum grounds become their classroom.

For Rain Crowley, a Sociology and Anthropology major from Galloway, archaeology has given them much more than a window into the past. They have bonded with their father and gotten physically stronger.

Crowley took Hornbeck's class as an elective their first year and changed their major.

"My dad has talked about loving archaeology many times, and I wanted something to bond over. That class made me realize how much I love archaeology and find the whole thing extremely fascinating. I’m very grateful to both of my parents for being extremely supportive and encouraging me to pursue archaeology," they said.

They've enjoyed gaining hands-on experience with excavation as an undergraduate and overcoming the physically demanding aspects of field work.

"While it’s a great experience and lots of fun, lifting buckets of dirt and kneeling or squatting for hours a day left me incredibly sore. The plus side is, I know for a fact I gained muscle because of this class," they said.

Stockton added a minor in Archaeology last fall. View the photo story below to see students uncovering Cape May County's past.

Photos and story by Susan Allen

Robynn Burge points to an artifact in the classroom during the early part of the semester. One of the first lessons Hornbeck teaches is how to read a landscape. Vegetation, divots and slopes are all clues that can explain what the land may have once been. Before students started digging on museum grounds, they choose three suspicious locations to investigate. They also learned how to curate artifacts in the classroom before working in the field.

Ceramic sherds are weighed on a scale.

A student examines a cat's-eye marble.

Rain Crowley uses calipers to record length and width measurements.

So far, students have found a lot of earthenware remnants of plates and bowls, ceramic sherds, glazed redware in the colonial Philadelphia style, iridescent pearlware and rusty nails dating from the 1700s to the 1940s. The most significant find is the first and only Indigenous projectile that would have been used to hunt small game.

Hornbeck has an 1841 property division map that shows an unlabeled structure on the museum grounds. There is no building there anymore. Was it a store, slave quarters or used for shipbuilding? Artifacts can eventually reveal an answer.

Sage Rosenberg, left, and Bobbi Hornbeck work inside a circular shaped depression on the property that waved a red flag for human interruption of the ground. Initially the class thought the depression could be a cistern that would have collected rainwater, but further research is leading them to a late 19th century septic tank since the clay pipe leads to the house.