Picture Stockton... Exploring the Cape May Coastline

Cape May, N.J. - During fall migration, warblers, raptors and monarchs flying down the East Coast funnel through the Cape May peninsula. Jason Kelsey and students in his Coastal Ecosystems class followed a sliver of their migratory route to learn more about habitats and differences in natural and developed coastlines.

With Cape May on National Geographic's top 10 list of birding destinations in the world, students packed binoculars for the field trip.

The class, part of Stockton University's Coastal Zone Management master's program, met at Higbee Beach wildlife management area to explore the natural bayshore and then took a short drive downtown to look at how beach engineering can reshape the coast.

Kelsey first took students to the Cape May Canal, home to the Cape May-Lewes Ferry, to climb up a mound of dry mud concealed by tall phragmite reeds. The canal is dredged to keep the channel deep for safe passage, and the mud is deposited on the Higbee Beach side of the canal. At the top, the sun-scorched mud cracked apart into fragments. Coyote prints revealed that the students weren't the only ones to explore the otherworldly landscape hidden by the dense vegetation that surrounds the base.

Casey Manera '21, an Environmental Studies graduate from Millville, N.J., has been visiting Higbee Beach since high school and "fell completely in love with all things wetlands" after taking Kelsey's Wetlands Ecology class a couple years ago. Now she's considering returning to Stockton for a master's in Coastal Zone Management.

The field trip led Manera to new perspectives on a familiar place.

"I always knew the dredge spoil hill existed but never viewed it as a valuable part of the land. Learning that the mud can house dormant seeds was super interesting, and this huge mudflat also serves as a time capsule. Kelsey explained that footprints can be preserved in layers of mud, which throughout millions of years, become fossils," she said.

Manera spotted one of the few plants that emerged from the mud cracks--a pickleweed. The edible salty succulent, sometimes served on salads, was slowing turning red, which is a sign that the plant can't hold anymore salt.

"I have such a deep connection to the marshes and barrier islands that pursuing a career to protect and manage these lands only made sense," she added.

Her career sights are set on working with coastal nesting birds, and she hopes to create a project monitoring gull species that utilize the marshes to study how climate change might be affecting their productivity.

"Conducting fieldwork is what gets me out of bed in the morning. I'm very fortunate to have had a class that gave me tools to excel in the field as well as problem-solve to discover species I would have otherwise overlooked," she said.

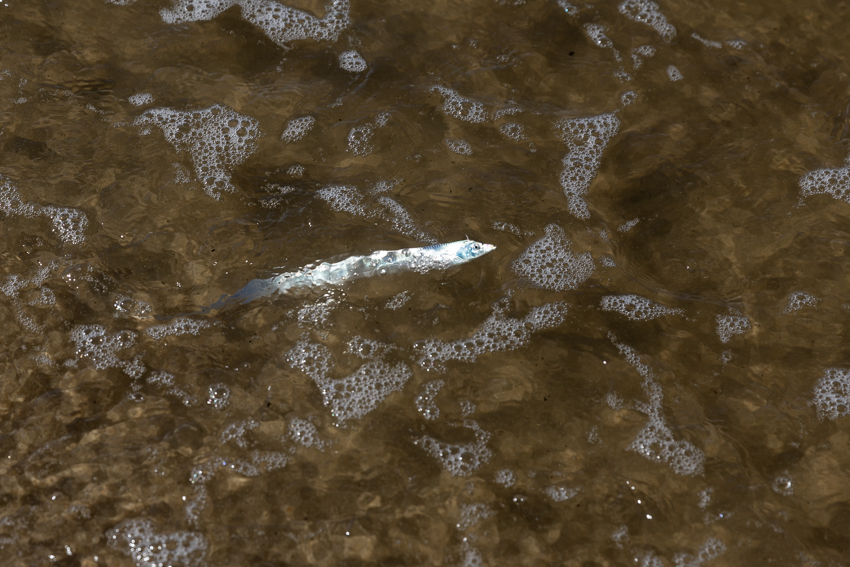

On the bay, a resident of the deep sea washed ashore. A slender and silvery Atlantic cutlassfish wriggled in the whitewater as the waves pushed it onto the sand briefly, offering the class a rare look at the eel-like fish that flashed its fang-like teeth.

A hermit crab curled into a fragment of whelk shell, and yellow-rumped warblers, a late migrant, foraged through beach plum shrubs and the white fluffy seeds that were once the mustard yellow blooms of goldenrod.

Students collected quartz pebbles smoothed by the sea, known locally as Cape May diamonds.

A very different seascape revealed itself just a few miles away at the downtown beaches near the convention center. The scallop-shaped shoreline, drawn by the ocean depositing fans of sand between the series of jetties, tried to mimic the gingerbread trim decorating the Victorian homes across Beach Avenue.

Below is a visual recap of the field trip shared with snippets from Kelsey's lecture.

Photos and story by Susan Allen

Unlike most New Jersey beaches, Higbee Beach is sheltered by a thick maritime forest. Songbirds flock to the wooded stretches along the Delaware Bay, and while exploring, the class ran into the fall songbird monitor scoping the area for the Cape May Bird Observatory's official count.

After hearing reports of a jaeger, a pelagic seabird, Casey Manera '21 looked for it and other shorebirds. Manera majored in Environmental Studies and joined the field trip as a guest. Since graduating, she has worked as a biological technician for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on Chincoteague Island in Virginia and as a research assistant for Point Blue Conservation Science on the Farallon Islands to monitor breeding Northern elephant seals as well as other pinniped and bird species and salamanders.

There's a scientific reason behind Cape May being the hot spot for quartz diamond hunters. "As soon as the Delaware River water hits the Atlantic Ocean, it’s like hitting a wall. The sediment starts to drop. The sand that accumulates along the Delaware Bay side of the Cape May peninsula has a high degree of sediment that has been deposited by the Delaware River. You’ll see pebbles on the beach. Pebbles don't usually exist on an ocean beach, but you see them here. The famous Cape May diamonds are the polished quartz crystals that are larger and haven’t fully weathered down to become the smaller, true sand grains," explained Kelsey.

The bayshore was mostly unoccupied by beachgoers, but wildlife will be moving in soon. "This sheltered bay is winter refuge for a lot of migratory seabirds and waterfowl. You’ll see all kinds of smaller shorebirds, like purple sandpipers and overwintering shorebirds, on the jetties. They pick off the invertebrates and algae encrusting the rocks," said Kelsey.

A disoriented Atlantic cutlassfish wowed students as it washed ashore giving them a rare glimpse at a deep sea fish. Luckily, it mustered the strength to fight its way back out to deeper water. Emily Zembricki, of Hazlet, N.J., was excited to see a species she's never observed. She joined the Coastal Zone Management program after earning degrees in Marine Science and Sustainability. "I want to be able to advocate and protect the places I am passionate about and the creatures there that I care for. I have a specific interest in charismatic megafauna, specifically marine mammals, and I believe my degree will help me protect them," she said.

Kelsey demonstrated how easily phragmite seeds disperse and ride the winds to their final resting spots where they will take root.

The surface of the dredge spoil is an ever-changing landscape. After a rain soaks the dried mud, the cracks disappear and later reappear as the drying process draws a new pattern.

A yellow-rumped warbler paused in the branches long enough to be captured for this photo story.

Students found vegetation from seeds that were stored in the bay mud.

After a short drive, students crossed the Promenade walkway to observe managed beaches.

Kelsey points out the scalloped edge of the coastline that results from sand deposition between the jetty structures.

One of the environmental issues that Kelsey spoke about was how changing weather patterns are affecting shorebirds. "Migration is timed critically. In the spring, shorebirds come up from the south end of South America. They start moving up the eastern seaboard, and the flyway that’s on the eastern portion of North America is probably the largest migratory path in the world in terms of biomass. The shorebirds make it to the Arctic to their breeding grounds where they nest and lay their eggs while the tundra is still frozen. Their eggs hatching is timed perfectly to the tundra thawing, and as the tundra thaws, all the insects start to emerge from the permafrost, so you have this dense swarm of insects, high in protein, that the parent birds are able to forage for very easily and feed their chicks. But what’s happening is that the tundra is freezing and thawing earlier, so by the time the eggs hatch all those insects have dispersed. They have to forage for other lower quality sources of nutrition, and what this is actually doing is resulting in birds with shorter bills—beaks that are not able to do what they are supposed to do. As an adult it limits their ability to forage because they can only forage in areas that aren't as deep or forage off of algae as opposed to the barnacles that are fully submerged. There will be weaker and fewer individuals in the population to complete the migration and reproductive cycle," said Kelsey.

View more photos on Flickr.