Stockton Poll: Food Insecurity in Atlantic County

Galloway, N.J. – Even before the pandemic closed businesses, a significant percentage of Atlantic County residents struggled to properly feed themselves and their families according to a Stockton University poll done in early March and released today.

Nearly one in five residents (18 percent) said they have run out of food and did not have the money to buy more right away, while 14 percent have skipped a meal because they could not afford to buy food, according to the poll. Among those with children, 17 percent have skipped a meal so that their children could eat.

More than one in three residents (35 percent) have eaten the same thing for several days in a row because that item costs less, according to the poll. Nearly one-third (30 percent) wished they could eat more healthy meals but cannot afford the cost, while 19 percent wished they could eat more fruits and vegetables specifically, but could not afford them.

The problem of food insecurity is greater in the county’s urban areas, especially in Atlantic City, and among ethnic and racial minorities, the results show.

The Polling Institute at the William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy at Stockton conducted the poll in early March, before New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy ordered non-essential businesses, including Atlantic City’s casinos, to close to slow the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus. Since then, thousands of unemployed families have waited on food distribution lines for free meal kits.

“These results show that food insecurity was a problem even before this public health crisis,” said John Froonjian, executive director of the Hughes Center. “A significant population struggled to feed their children and eat healthy meals even when the local economy was booming, and the problem will likely persist when the good times return.”

The poll of 827 adult residents of Atlantic County, N.J., was conducted March 7-13 by the Polling Institute of the William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy at Stockton. The poll’s margin of error is +/- 3.4 percentage points at a 95 percent confidence interval.

The vast majority of county residents have easy access to food, with 97 percent living within 10 miles of a supermarket, 94 percent finding it convenient to get to one, and 99 percent reporting that there are healthy food options at the store from which their household buys food.

Though food may be convenient to access for most Atlantic County residents, affordability was a barrier to food security for some, said Alyssa Maurice, research associate for the Hughes Center. Low food security is defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as “reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet with little or no indication of reduced food intake,” while very low food security is characterized as “disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” The poll found instances of both low and very low food security among some residents.

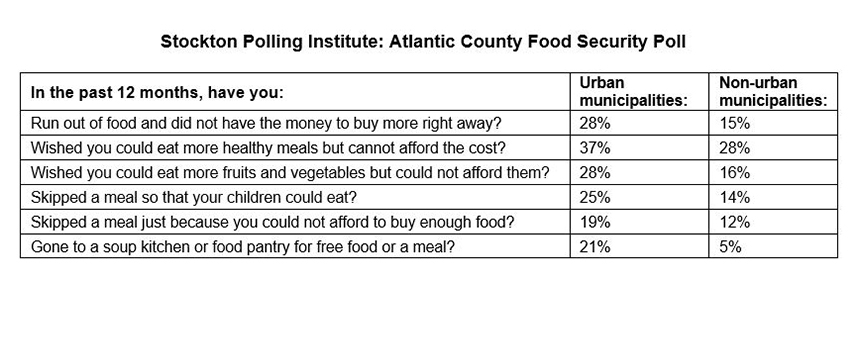

Atlantic County residents living in urban municipalities (Atlantic City, Pleasantville, Ventnor and Egg Harbor City) are more likely to face food insecurity than those in suburban and rural locales. According to the poll, 28 percent of those in urban municipalities have run out of food before they had the money to buy more, compared to 15 percent of those living outside these cities.

Similar discrepancies were found between residents living in Atlantic City and Ventnor and those in the remaining parts of the county. For instance, 25 percent of Atlantic City-area residents have gone to a food pantry or soup kitchen for free food or a meal in the last year, while only 6 percent of residents outside Atlantic City say they have.

The poll also found consistent racial and ethnic disparities on the issue of food insecurity. More than twice the rate of Hispanic or Latino residents (34 percent) have run out of food and not had the money to buy more than non-Hispanic or Latino populations (15 percent). Further, 45 percent of Hispanic or Latino residents have wished they could eat more healthy meals but could not afford to, while 28 percent of remaining populations say the same.

In terms of racial disparities, 9 percent of white respondents, 21 percent of black/African American respondents and 22 percent of respondents who are more than one race have skipped a meal because they could not afford it. A similar racial gap is found among other measures of food security, including those who rely on soup kitchens or food pantries, with 7 percent of white residents having gone to one for free food or a meal, whereas 18 percent of black/African American residents and 14 percent of non-white residents overall have.

Senior citizens tend to have higher food security than younger residents. More than one in five poll respondents younger than 50 report having been unable to afford buying more food or eating healthier. Still, more than one in 10 adults aged 65 and older at times have not been able to afford more food when they run out or to buy more fruits and vegetables. Maurice noted that any percentage of more than 10 percent reflects a significant population.

Food security increases in tandem with both income and education levels, which are significantly correlated. Half of residents with a household income less than $25,000 have run out of food before they could buy more. The rate decreases substantially as household income increases, with 30 percent of residents in households making $25,000-$50,000 and 9 percent of those in households making $50,000-$100,000 experiencing this. This pattern is consistent across various measures of food security when broken down by household income.

Similarly, 25 percent of residents who did not graduate high school have run out of food before they could buy more. That rate decreases only slightly for those who graduated high school or vocational schools, and those with some college or an associate degree, both at 22 percent. It decreases substantially among those with a four-year degree, with 12 percent of these residents having run out of food before they were able to buy more. Among those with a graduate degree, it drops further to 8 percent.

“It’s heartbreaking to see so many families on food lines during the current crisis. We should remember that for many people in our own back yard, this is an everyday reality,” Froonjian said.

The Hughes Center is conducting additional research on the food insecurity issue this summer.

Complete poll results are at stockton.edu/hughes-center

METHODOLOGY

The poll of Atlantic County, New Jersey adult residents was conducted by the Stockton Polling Institute of the William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy at Stockton University. The telephone survey was conducted on March 7-13, 2020. Live interviewers who are mostly Stockton University students called cell phones and landlines from the Stockton University campus. Overall, 91 percent of interviews were conducted on cell phones and 9 percent on landline phones. Both landline and cell phone samples were called from random digit dial samples obtained from MSG. A total of 827 adults were interviewed who were screened as residents of Atlantic County. Data designated as coming from urban areas were comprised of responses from Atlantic City, Ventnor, Pleasantville and Egg Harbor City. Data were weighted based on the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey data for Atlantic County, New Jersey. Differences between the number of respondents polled and total responses shown in results tables are the result of data weighting. The poll’s margin of error is +/- 3.4 percentage points at a 95 percent confidence interval. MOE is higher for subsets.

About the Hughes Center

The William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy (www.stockton.edu/hughescenter) at Stockton University serves as a catalyst for research, analysis and innovative policy solutions on the economic, social and cultural issues facing New Jersey, and promotes the civic life of New Jersey through engagement, education and research. The center is named for the late William J. Hughes, whose distinguished career includes service in the U.S. House of Representatives, Ambassador to Panama and as a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Stockton. The Hughes Center can be found on YouTube, and can be followed on Facebook @StocktonHughesCenter, Twitter @hughescenter and Instagram @ stockton_hughes_center.

# # #

Contact:

Diane D’Amico

Director of News and Media Relations

Galloway, N.J. 08205

Diane.D’Amico@stockton.edu

609-652-4593

609-412-8069

stockton.edu/media