Life’s a Beach When You Dive into Your Passion

Fall 2021 Issue

Volunteers assisting with restoration of an eroded shoreline at Slade Dale Sanctuary in Point Pleasant, NJ. Photo Credit: American Littoral Society.

When South Carolina native Alek “Capt. Al” Modjeski ‘98 joined the Air Force during Desert Storm in the late 1980s, he left the warmth of southern hospitality and landed his first assignment in the hustle and bustle of New Jersey at McGuire Air Force Base (MAFB). His military career would take him to places he knew he would never see again, and at the time, New Jersey was on that list.

“My parents had always told me not to come home – to go out and see the world,” Modjeski said of a discussion he had with his parents before heading to boot camp. When his stint in the military was over, Modjeski was yearning to return to his home state to enjoy the warm weather and outdoor activities he appreciated growing up, but his parents’ words echoed in his mind.

Wanting to explore the world when his tour was over, he needed to earn some money. He found himself back in New Jersey working as a dispatcher at a limousine company in Atlantic City with a childhood buddy from Myrtle Beach. He quickly realized he wanted more out of life than just dispatching limousines and needed to create new opportunities that would allow his future family the type of lifestyle – outdoor activities with the beach nearby – that he had been so gifted to have growing up in Myrtle Beach.

Modjeski heard about Stockton and enrolled in his first course at the University – a geology class with Mike Hozik. Studying at the University opened a world of experiences for the young Modjeski – from traveling to Costa Rica with his ecology class to exploring the waters of South Carolina for new fish species with mentor Rudy Arndt during spring break. “We actually found the distribution of inland silverside where they didn't even know it existed. I was able to be a part of all this really cool stuff as a young college student,” Modjeski explained.

He was hooked. Modjeski could see his future as a marine scientist and decided he was going to make the most out of his educational experience. He took various part-time positions to gain as much hands-on experience while attending Stockton– working with the state [New Jersey] on an artificial reef project, as a first mate on a recreational fishing boat, and as a student worker at the Marine Field Station. In addition, he earned his Captain’s license through the U.S. Coast Guard where he had a unique opportunity to discover pelagic fish along the New Jersey coast [Pelagic fish live in the pelagic zone of ocean or lake waters – being neither close to the bottom nor near the shore – in contrast with demersal fish that do live on or near the bottom, and reef fish that are associated with coral reefs. Wikipedia]. “I also had a wonderful opportunity working on the New Jersey Trawl Survey… I learned everything through so many different people,” Modjeski explained.

After graduation, Modjeski knew returning to the South would be challenging because of the established relationships he made in the Northeast. He sought employment in both the public and private sectors and his earlier artificial reef restoration work proved useful in securing a position with a private firm – The Louis Berger Group out of East Orange. “I had already had some solid hands-on experience [with the state], and now I was building [artificial reefs] in Puerto Rico, assessing environmental issues in Hong Kong and ensuring impacts to marine life were minimized in Guatemala. All these different things started happening where I had this evolving breadth of scope with global reach to help me apply the knowledge I gained from Stockton,” Modjeski explained.

Through his years working in the private sector, he continued to establish new relationships with other professionals in nonprofit organizations (NGOs) as an acting member of commissions and committees. Modjeski had a desire to develop ideas that would help others. To fulfil that dream, he knew he needed to be in the public sector but was having difficulty landing a position.

He had associated with colleagues from the American Littoral Society in the past, so when he received a lead in 2014 advising of an opening, he knew he had to jump on it. [The American Littoral Society is a not-for-profit corporation aimed at the study and conservation of marine life and habitat, protection of our coastline, and promotion and education of the value of conservation programs.]

“The former habitat restoration program director had called me to let me know he left the American Littoral Society. He said I've always been kind of a fan of what you guys do; you might want to apply [for the position]. Before we even got off the phone, I had already sent my resume,” Modjeski said.

When Modjeski came into the position, he oversaw $13 million in resiliency projects intended for the rebuilding of the Delaware Bay and beaches for the horseshoe crab, red knots, oyster reef restoration and outreach. Over the years, Modjeski has received grants to amass resources and the small fleet needed to conduct science-based habitat restoration. Today, he sits on many state and national committees for resiliency and restoration and in March 2021, Modjeski provided congressional testimony at an oversight hearing before the Committee on Natural Resources regarding habitat restoration as a programmatic long-term investment.

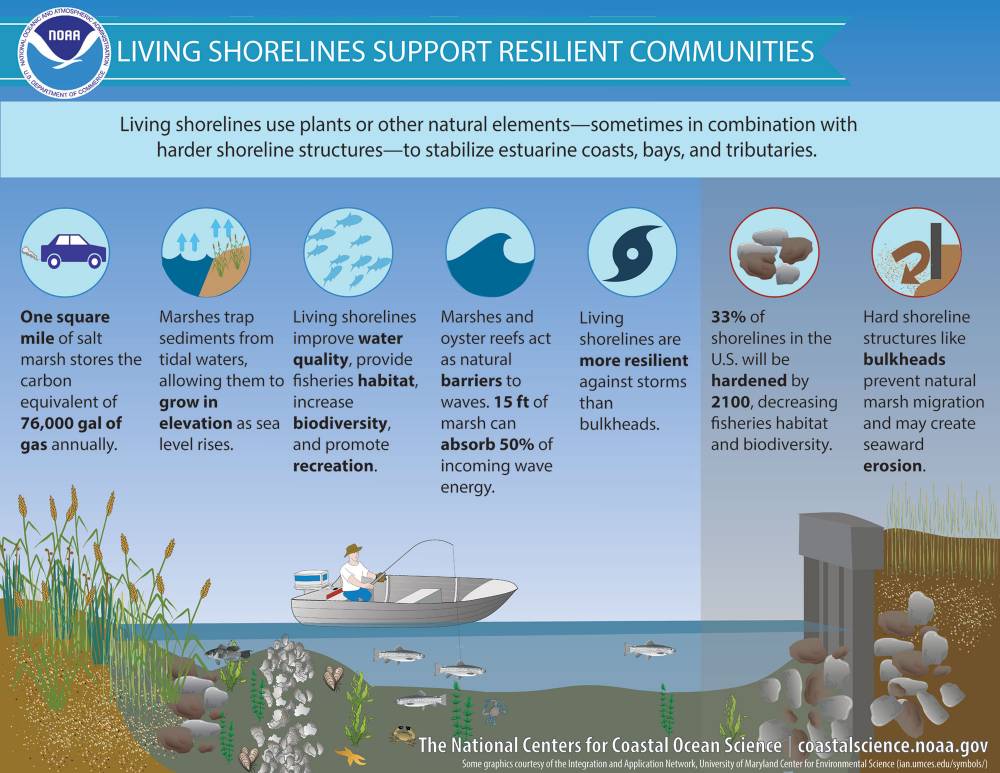

Saving Our Beaches with Living Shorelines

In the early days of conservation, hard structures such as jetties or seawalls were the preferred method for reinforcing shorelines from erosion. Over the past few decades, these manmade structures were found to cut off areas further down the beach from natural longshore drift, causing or worsening erosion in these areas. With this discovery, many coastal and lakeside states have adopted the use of living [soft] shorelines as the primary preservation technique – a few banning the construction of new hard structures as solutions for erosion control.

“Capt. Al” [Alek] Modjeski and his team at the American Littoral Society (ALS) are keeping busy restoring New Jersey beaches, shorelines and marshes through the creation of nature-based techniques which are not only beautiful but functional, providing ecological uplift and improved resiliency to adjacent communities.

One of many restoration projects on their list is the restoration of Forked River Beach in Ocean County. Since 1995, Forked River Beach has lost over 120 feet of shoreline –approximately 6 – 12 feet lost this year alone – causing damage to both the ecosystem and residential damage. With a $1M grant from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), Modjeski and his team are restoring Forked River Beach.

As the shoreline erodes, it creates turbidity in the water where there is a significant rate of erosion. [Turbidity is the measure of relative clarity of a liquid. – USGS.gov]. With the funding, Modjeski explained they can build “intertidal [intertidal: the area where the ocean meets land between high and low tides – NOAA] and subtidal [subtital: portion of tidal-flat environment which lies below the level of mean low water for spring tides. Normally it is covered by water at all states of the tide – Everthingwhat.com] oyster reefs that would encapsulate the town of Lacey Township and Forked River Beach to reduce erosion and improve water quality.” Over time, the reefs will promote resiliency of the community [oysters] that’s there.

New Jersey has a history of promoting a natural strategy when looking at coastal management, but more recently, the NJDEP has been able to implement guidelines stating living shorelines should be the first option when looking at retoration.

Natural materials such as sand, rock, plants and oysters are a cost-effective solution for coastal management and will benefit the local ecosystem over time.

"It's expensive to do the hard structures in comparison to a living shoreline piece...you want to soften or hybridize the shoreline to meet the goal…[otherwise,] you may miss getting the attachment of certain shellfish. You may not get the refugia for fish you need and the continued resiliency,” Modjeski explained. “You try to figure out how you’re going to do this on a natural level. If you're in a high-energy environment, you must evaluate and do your monitoring ahead of time – get the baseline data so you have a better idea of the way to go.”

Modjeski said they were hopeful they could add “about 30,000 to 35,000 tons of sand one day at Forked River Beach, then [we’ll] add a vegetated berm [vegetated berms: compacted or vegetated structures designed to slow, pond, or filter runoff; divert runoff on a construction site to a sediment trap/basin; and/or ensure clean upland runoff does not move into disturbed areas – augustachronicle.com] behind that beach to improve the resiliency even more for the residents there, as well as uplift some of that ecology that's struggling.”

Natural coastlines have been around much longer than the hard structures and survive storms better. That says something.”

News of their efforts has reached municipalities like Seaside Park and Lavallette – both of whom are in jeopardy of losing their shoreline and ecology due to flooding and storms. “They want to do something living that is good for the environment. All the work we’ve been doing is catching on; people are taking an interest,” Modjeski exclaimed.