Stockton to Monitor New Mill Creek Oyster Reef

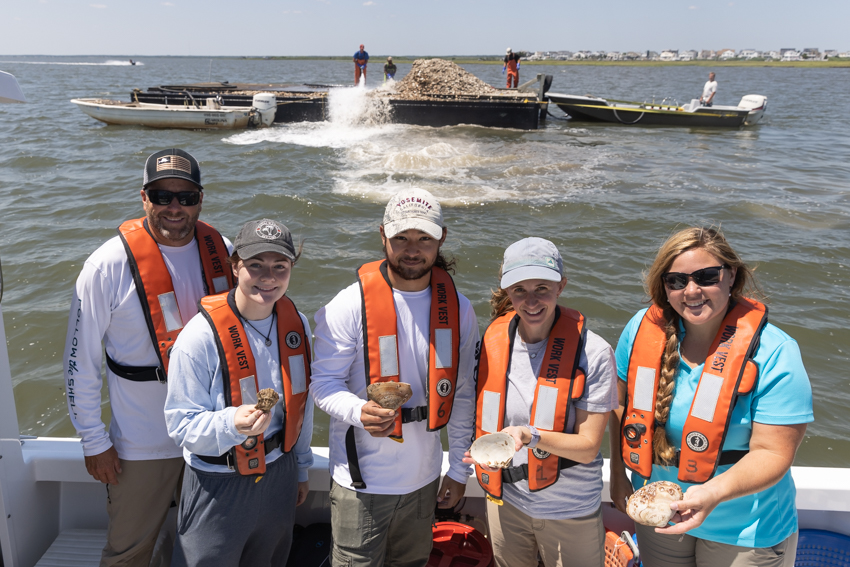

From the R/V Rudy Arndt, Christine Thompson, Steve Evert and students watch the planting of the new Mill Creek oyster reef in the Barnegat Bay.

Manahawkin, N.J. - A mound of more than 1,000 bushels of surf clam shells speckled with growing oysters tumbled overboard into the Barnegat Bay as they were sprayed off a barge to form the Mill Creek oyster reef. The new restoration site will be monitored by the Stockton University Marine Field Station.

Restoration Efforts Expand with a Second Reef

Christine Thompson, assistant associate professor of Marine Science, and students will track the growth and survivorship of the oysters and how they improve water quality. The oysters were planted by Dale Parsons, a fifth-generation oyster farmer of Parsons Seafood in Tuckerton.

“The purpose for this reef is to enhance oyster populations in the Barnegat Bay. It’s here for restoration to bring back ecosystem services such as habitat and water quality benefits. It’s a sub-tidal reef with everything planted on the bottom, and we will be monitoring it starting this fall,” said Thompson.

The 1-acre reef, funded by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection with support from the Jetty Rock Foundation, is located between Beach Haven West on the mainland and Ship Bottom on Long Beach Island.

The new reef is a few miles away from the Tuckerton Reef, the first restoration site in the southern Barnegat Bay planted in 2017. Stockton has been monitoring and learning from the Tuckerton Reef and using it as a platform for research projects.

Students Isiah Cruz and Colleen Heffernan were aboard the R/V Rudy Arndt to witness the planting.

“It felt really good to see this come together,” said Cruz, who has been visiting the site since the semester ended in May to help monitor the water quality and collect oyster samples from the Tuckerton reef to measure them and compare the results to previous years.

Heffernan agreed, adding that “after all the preparation, it was exciting to see the planting.”

Virginia-Born, Jersey-Raised Oysters

Some of the oysters growing on the new reef were spawned and raised at Oyster Seed Holdings, a hatchery in Virginia where two Stockton Marine Science alums now work.

Alexandra Blanchet ’18 is an algologist, which means she grows various species of algae to feed larval oysters. She admits it can be a dirty job, but it’s one where she’s always learning, constantly moving and never the same.

She works with tiny microalgae species since she has tiny mouths to feed. She described the algae species she grows as resembling a green smoothie and black coffee.

Her earliest experiences with oysters were around the table at the Marine Field Station looking through a magnifying glass to count spat (oyster larvae that has set onto a surface) and sifting through plankton nets during bivalve larvae sampling in the Mullica River.

When larvae for the Mill Creek reef were sourced from the hatchery she works at, she realized she had come full circle. “It’s really nice to see,” she said.

Samantha Glover ’18 is the manager of research and development and collects data and oversees projects and collaborations with Oyster Seed Holdings.

A combination of courses like Invertebrate Zoology and Fisheries Management and a Stacy Moore Hagan Memorial Scholarship internship allowed her to learn more about the creatures she grew up watching at the beach.

Glover explained how the Mill Creek oysters spent their first days.

From the time they are fertilized to day six, the oysters are vulnerable and are kept in a cylindrical tank filled with water that is aerated. The free-swimming larvae are then transferred to flow-through cones where they get constant seawater and food. When they are ready to set on a hard substrate, they transform into eyed-larvae and their foot begins to emerge.

“A spot that can detect light forms to tell them where the light is coming from and helps them orient themselves within the water column,” she explained. Once they know which way is down, they search for a place to settle for the rest of their lives.

When Dale Parsons received the eyed larvae, he released them in tanks filled with cages of surf clam shells for the larvae to attach themselves.

Finding a Place for Oysters to Thrive

Thompson and Steve Evert, director of the Marine Field Station, worked together to select a suitable site for the new reef.

Larval dispersal models suggest that the bay near the Route 72 Causeway bridge can potentially catch more recruits from oyster larvae, Thompson explained, adding that “anecdotal observations have spotted natural settlement of oysters in that area on pilings and bulkheads.”

Deeper water was chosen to avoid competition with seagrass, which needs water shallow enough that it can still absorb enough sunlight for photosynthesis.

“We needed to have a firm bottom. It can’t be too silty because the shells would just sink and get covered,” she explained.

Evert’s knowledge of the local waters paired with research and boat rides seeking the right habitat ended with a spot that is visible from the bridge.

Watching the Water to See the Impact

Thompson picked up a single surf clam from a basket holding a sub-sample of the oysters being planted. More than a dozen spat decorated the otherwise empty clam shell.

Back at the Field Station, she and students closely examined the sub-sample to get precise spat counts to estimate how many oysters were planted on the reef.

Oyster density, size and survivorship data will be collected later this fall.

Water quality improvement will be tracked by measuring parameters like pH, dissolved oxygen, salinity and turbidity.

The data from the Mill Creek reef will be compared to a bare bottom control site as well as the Tuckerton Reef.

As oysters grow, they can filter more water. With a second reef in the bay, there is greater filtration ability and more habitat for wild oysters to populate.

As the Jetty Rock Foundation website states, “an oyster a day is great for the bay.”

Visit the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics and the Marine Field Station to explore the majors and research opportunities at Stockton.

Story and photos by Susan Allen