Researchers Fish for Answers to Striped Bass Migration and Stock Origins

Adam Aguiar, assistant professor of Biology, leads Cedar Creek High School students on a fishing experience on the beach in front of Stockton Atlantic City during the New Angles for Success program.

Galloway, N.J. - Silvery metallic Atlantic striped bass have seven to eight dark lines that stretch from their gills to their tail, but there are some that also have an extra yellow stripe trailing from their backs. These fish were caught and tagged in New Jersey waters by Stockton University researchers and will help explain the species’ life history and migration when they are caught again.

Since last fall, Adam Aguiar, assistant professor of Biology, and his research students have caught and tagged 65 Atlantic striped bass. Those fish now wear a yellow tag that looks like a piece of spaghetti noodle attached to their back just behind the second dorsal fin.

The researchers hope that anglers will recapture the tagged fish and report the unique codes written on the tags to the American Littoral Society in Highlands, N.J.

Beachfront Classroom Leads Students to Research Opportunity

Aguiar started the Striped Bass Tagging for Stockton research group when students in his general studies course, “Ecology and Saltwater Fishing,” wanted to learn more and get field work experience.

Stockton Atlantic City, where Aguiar offers the course, is within the region that anglers call the Striper Coast, an area of striper abundance that stretches from Cape Hatteras to Cape Cod.

Aguiar once went 86 consecutive months catching at least one striped bass per month, but it wasn’t a lucky streak. He meticulously logs tides, temperatures, moon phases, weather and more to identify the specific combination of conditions that signal striper feeding and how those patterns evolve over time.

Jared Handelman presents findings on the stock origins, micro-habitat preferences and population health of striped bass at the NAMS Symposium.

Fish tagging offers researchers data that can’t be directly observed, and for aspiring biologists, it’s also an opportunity to get experience for a future career.

Grant Johnson, Jared Handelman, and Matt Pagano were research students last semester during spring spawning, and Dylan Garranbrant was a research student during the fall migration.

Handelman, a sophomore Marine Biology major, wants to become a biologist, and Garranbrant, a senior Marine Science major, wants to work in fisheries science focusing on striped bass.

Johnson, a sophomore Environmental Science major, got involved to make his catches contribute to science. “I knew I was capable of collecting a great amount of data, which in turn gives myself and other anglers more knowledge on a species that I have loved my entire life,” he said.

Striped bass are essential to the marine food web and are a popular game fish species for food and recreation, generating the bulk of revenue for many fishing-related industries, Handelman explained in a poster that he presented at the NAMS Symposium. He also noted that stock assessment data from his research suggests a sharp decline in striped bass numbers.

Environmental changes, pollution and disease can alter migration behavior and impact population health, and tagging research reveals how these factors play into the striped bass story with every recapture.

Catching Clues to Migration

When the tagged fish are recaptured, the team begins to get data points. Knowing when

and where the fish are caught allows the team to determine where they go to spawn,

where they spend their winter and their growth and survival rates.

When the tagged fish are recaptured, the team begins to get data points. Knowing when

and where the fish are caught allows the team to determine where they go to spawn,

where they spend their winter and their growth and survival rates.

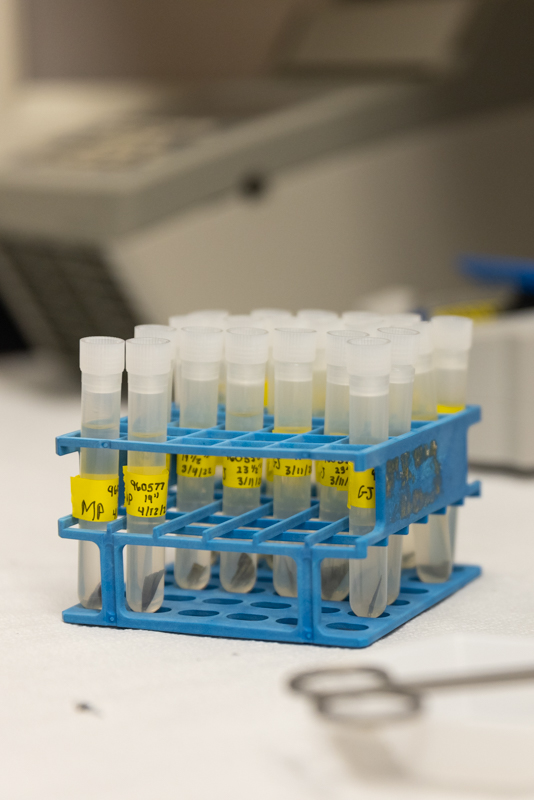

For each fish tagged, the researchers record the date, location and conditions, and measure the fish and take a caudal (tail) fin clipping and scale sample.

Just like a tree is aged by counting concentric rings, fish can be aged by counting the annuli (rings) on a scale that become visible under a microscope.

Striped bass are anadromous, meaning they spend most of their life in saltwater and migrate to freshwater to spawn. The fish caught in New Jersey originate from one of three main spawning grounds in the Chesapeake Bay, Delaware River, and Hudson River.

Aguiar and his students are focusing their study on fish that swim off the coast of Long Beach Island, which are a mixed-migratory stock, meaning that they can originate from any of those main spawning grounds as well as micro spawning grounds.

The fin clippings hold the answer to where the fish were born.

Finding Stock Origins in Fin DNA

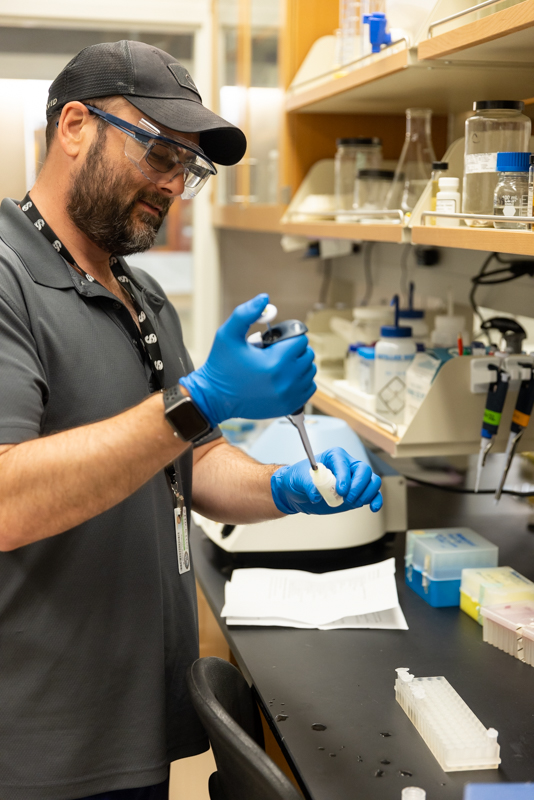

Inside a lab in the Unified Science Center I, Aguiar held a fin clipping with tweezers. “The fin is made up of cells that have DNA and we want to extract that DNA,” he explained.

The challenge is the size. “The DNA particles are so small. We chemically and mechanically separate the DNA from all the other material,” he said.

Aguiar had bottled chemicals lined up on the counter to help him liquify the fin, so he could separate, extract and purify the DNA with the help of a centrifuge, Nano Drop (a piece of equipment that quantifies DNA, RNA and protein samples) and RNA-eating enzymes.

Next to his supplies was a page of steps carefully listed in a precise order. “Science is kind of like cooking,” he laughed, as he checked the recipe.

When Aguiar is left with just the DNA from the fin clipping, he can then use other lab tools and techniques to read the part of the sequence that codes its origin.

Views for the Lab of a DNA Extraction

Turning a Passion into a Career and Inspiring the Next Generation

Matthew Pagano, who is working at TAK Waterman Surf 'n Fish iin Long Brach this summer, learned to fish from his dad, and over the years, that hobby turned into a lifestyle.

“When I was picking classes for the previous fall semester, I stumbled upon a class called ‘Ecology and Saltwater Fishing,’ and I just knew I had to take this course. I went in with an idea of what I would be learning but to my surprise, I learned much more than anticipated,” he said.

Now as a student researcher, he’s learning how to turn that lifestyle into a career.

After learning the delicate process of tagging on a fluke tagging trip led by the American Littoral Society with Aguiar and other students, he safely caught, tagged and released a 47-inch striped bass.

Garrabrant also remembers that fluke tagging trip. He tagged his first fish that day. He later tagged 12 bass in Barnegat Bay, which is his most productive night to date.

This summer, Garrabrant has an internship in Jonesboro, Maine working for the Department of Marine Resources. He’s researching Atlantic salmon and identifying areas of temporal refuge for both adults and juveniles, since they seek out cooler water to avoid heat stress.

He started tagging fish at Stockton, and he’s not planning on stopping. “I plan to continue tagging striped bass long after college—for as long as I am able to fish for them,” he said.

The Stockton tagging group also works with Atlantic City youth through the New Angles for Success program to introduce local students to the fishing opportunities in their hometown.

“On the Atlantic City Boardwalk, we taught angling basics and techniques, aspects of beach and outdoor safety, the importance of the marine environment and its natural resources, as well as the importance of higher education,” Jared Handelman explained.

Aguiar’s course has applications beyond fishing. Johnson said, “Professor Aguiar has taught me a lot, while at the same time making me work to achieve goals, and has shown me that with a scientific mindset, you can optimize your results of fishing trips and anything else in life.”

A Stockton Osprey Leads Littoral Society Fish Tagging Program

Emily McGuckin, a 2018 Marine Science graduate who is now the fish tagging program director for the American Littoral Society, was excited when Aguiar reached out to involve students in tagging.

She met the Stockton team on the Littoral Society’s annual fluke tagging trip last summer, which became a memorable learning experience for the students.

“On the trip, I really got to know Dr. Aguiar and the other kids in the program, who would soon become some of my closest friends,” recalled Grant Johnson.

Having a group of anglers fishing near Stockton as well as their hometowns provides data that covers a lot of territory, McGuckin explained.

The program she now directs has tagged about 967,000 fish since it started in 1965. The data, which is sent to the National Marine Fisheries Service at Woods Hole and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, is showing evidence that “fish are starting to migrate north due to the warming temperatures,” she explained.

Scientists use the data to make decisions on fishing rules and regulations for populations in specific locations.

As a student, McGuckin got research experience with a Stacy Moore Hagan Memorial Scholarship internship and a fish tagging internship with the Littoral Society.

“They might not know it, but Mark Sullivan and Anna Pfeiffer-Herbert helped me figure out what I was looking for. I wouldn’t be here at the Littoral Society if I hadn’t gone to Stockton,” she said.

McGuckin has come full circle and is now sharing her knowledge as an intern supervisor for Emily Zembricki, a senior Marine Science major at Stockton.

The most exciting days are still ahead as McGuckin and the research team patiently await recapture data.

Story by Susan Allen

Photos by Adam Aguiar and the tagging researchers